Sheep ranchers look into ‘targeted grazing’

On a harvested wheat field in Yolo County, Don Watson’s “wooly weeders” hungrily chomp on a gourmet feast of invasive plants that have overtaken the property.

The landowner pre-irrigated the field to let the weeds to grow out before Watson put his sheep to work on the land. The idea is to allow the animals to clean up the field rather than using herbicides.

“This is just a symbiotic quid pro quo that we’re doing,” Watson said. “We gain on the lambs and they’ll gain from how (the lambs) are inoculating the soil with manure, which acts as a fertilizer.”

Watson, who spoke last week at a workshop on targeted grazing, currently operates two businesses: Wooly Weeders, which provides grazing services for vegetation management, and Napa Valley Lamb Co., which produces meat and wool.

The California Wool Growers Association held the workshop in Woodland to help educate producers about the potential profitability, as well as the legal and financial risks, associated with adding grazing services to livestock operations.

Though still a relatively new idea, using livestock such as sheep and goats to control weeds and brush has gained attention and popularity in recent years. Watson called his grazing business a good complement to his ranching operation that provides another important revenue stream.

He said before getting into the grazing business, he was actually losing money selling meat and wool. Today, he said he nets a profit.

“It’s not something that you’re going to get rich on,” he said. “You’re going to make a living and it’s a great lifestyle, but chances are you’re not going to be very wealthy.” Read More

Rancher finds niche in Napa

The Napa Valley is synonymous with premium grapes and the best wines in the world.

The Napa Valley is synonymous with premium grapes and the best wines in the world. It’s also where you’ll find some pretty serious multi-tasking going on at Don Watson’s sheep ranch. Don has been raising sheep and cattle for nearly 20 years in the Napa Valley and elsewhere in California. But it wasn’t exactly what he set out to do. In 1986, he and his wife Carolyn ditched their high-paced city life in San Francisco for a life on the farm. After spending some time on sheep ranches in Australia, Don started his own.

Now the Watsons are respected suppliers of top lamb for upscale Bay Area restaurants including Chez Panisee in Berkeley and Oliveto in Oakland. Don also works closely with Victor Scargle, a chef at Julia’s Kitchen, inside the world-famous American Center for Wine, Food, and the Arts, Copia, in Napa. Victor says he loves working with fresh products, so having Don and his sheep so close is perfect for him. Because of the close proximity of Don’s ranch to Copia, Victor tries to put lamb on his menu as often as he can and he says the feedback customers have given him has been tremendous. You will often find Don’s sheep and lambs grazing in vineyards, including pioneer vintner Robert Mondavi’s. The animals provide effective, low-cost weed control, eliminating the need to spray herbicides and providing extra income for Watson.

While most people think of lamb mainly at Easter, California lamb is available all year long. In fact, California ranks among the nation’s top lamb states, although the entire business has taken a hit in recent years. To survive, many ranchers rely on niches and Don Watson is one of them. His animals are highly effective mowers, taking out weeds from places like Robert Mondavi’s prized vineyards. This system is not only extremely effective for the farmers, but for the vineyards as well. The “four-legged mowers” cost less than spraying chemicals in the vineyards and provides an excellent feed source for the animals, making it a “win-win” for everybody involved.

In his previous life, Don Watson crunched numbers on the 40th floor of a San Francisco high rise, another suit sipping cappuccino in the city’s financial district.

These days, dressed in Levi’s and work boots, Watson trails sheep through the vineyards of Napa and Sonoma counties. He raises fancy lambs to accompany the area’s pinot noir.

“It’s the freedom,” said Watson, 37, as he looked over the green hills of the Carneros, a windblown, grape-growing region on the southern edges of Sonoma and Napa counties.

Watson and his wife, Carolyn, are among a growing number of specialty sheep farmers producing young, high-quality lamb for expensive area restaurants. What separates Watson from the rest of the gourmet flock is that he lets his sheep forage in the vineyards during winter and early spring.

Carneros, which means sheep or ram in Spanish, provided undulating pastureland for more than 100 years before the grape invasion 25 years ago, when investors began buying up ranches and planting vines.

“Don has put the carneros back in Carneros,” said Karen Bower, viticulturist at Buena Vista Carneros, one of the vineyards where Watson’s 400 ewes graze from November until the vines begin sending out green shoots in early spring.

On a clear day, Watson can see the San Francisco skyline he left behind three years ago.

“I’m outdoors all day and I love it. Sure, it’s pouring rain and freezing cold on some days, but where else can you see such beautiful country every day?” he said.

A Calistoga resident, Watson often travels 150 miles a day within the two wine regions to run his sheep business, Napa Valley Lamb Co. Watson’s 2-year-old son, Donny, and 6-year-old daughter, Andrea, often tag along on the sheep trail.

“I get to see more of my children since I left the corporate world,” Watson said. His trademarked lamb is served in top local restaurants such as the Lark Creek Inn in Larkspur, Mustard’s Grill in the Napa Valley and San Francisco’s Fog City Diner.

Like long-ago shepherds, Watson moves his sheep from field to field, utilizing other peoples’ land. His ewes are bred to forage.

“We make no bones about it. We put them on the range and they have to make it. If they can’t get out and find their own food, we don’t want them,” he said.

From November when the vineyards go dormant until late March or early April, Watson’s sheep munch on mustard, clover and fescue in the avenues between the vine rows at the Buena Vista Winery’s Carneros vineyards in Sonoma County.

“These are weeder sheep,” said Watson.

The sight of the white sheep grazing has become a favorite subject for Wine Country photographers, who see it as European. But mixing sheep and vineyards is more than creating a bucolic backdrop.

“It’s really a practical thing to have sheep in the vineyards,” said Bower, adding that the sheep were invaluable during this unusually wet winter because they could get into soggy vineyards when tractors couldn’t.

“When the weeds in a vineyard are at waist level, there is more frost threat. Basically, the sheep do the first spring mowing for us,” she said.

Watson, a former accountant for Arthur Andersen & Co., wanted to be a sheep rancher ever since he was a youngster growing up in Stockton.

He wasn’t reared on a sheep ranch but had come to know many of the Basque sheep ranchers in the San Joaquin Valley and respected their simple, hard-working lifestyle.

So while most children were dreaming of careers as astronauts or football players, Watson had visions of herding sheep, sacking wool and wrestling lambs. He took the plunge after a career as an accountant proved as sterile as he imagined.

“You get to the point where there is more to life than money,” said Watson. He quit his accounting job and, with wife Carolyn, spent a year working on sheep ranches in Australia and New Zealand.

He worked on ranches with 10,000 ewes, quickly learning that to make a living with sheep one has to utilize the grass provided by Mother Nature and keep production costs down.

After they returned from Down Under, the Watsons moved to a 400-acre ranch on the southern slopes of Mt. St. Helena that belongs to his wife’s family. The land is rough, rocky and teeming with predators, such as coyotes and mountain lions.

Sheep wouldn’t last long on this ranch so he takes them on the road, using land between Napa and Petaluma for his roving flock.

Watson’s new career offers him blue skies, a chance to be outdoors and time to be with his family, but the money falls far short of an accountant’s paycheck in San Francisco.

Watson markets 500 to 600 lambs a year, with a gross value of $50,000 to $60,000.

A gang of coyotes earlier this year killed 100 lambs, a $10,000 loss. It doesn’t take an accountant to figure that the coyote attack will sharply reduce Watson’s hourly pay at the end of the year.

Still, he’s not ready to get back in his suit and pore over accounting sheets.

“I decided this is the life I want and I will make it work. If not here, then in New Zealand,” he said.

Driving up Adobe Road just outside Petaluma, cars slow to catch a glance at dozens of sheep munching their way through vineyards.

It’s not much of a show, really, but folks stop anyway for a glance or a photo now that the lambs are in tow. And though the flock will soon move to another location, right now these meandering puffs of wool are happy simply doing what they do best: eating hundreds of pounds of unruly weeds.

Despite their idyllic life, these sheep have an increasingly important role to play in the vineyard ecosystem. Instead of growers spending hundreds of man-hours toting around weed-eating machines or using hundreds of gallons of industrial herbicides, these four-legged nibblers do the job of several workers in less time, with less environmental damage, and often for significantly less money than it would cost to use humans, according to their proponents.

“It’s great having them pooping out in the vineyards,” says Ginny Lambrix pf Santa Rosa’s De LoacVineyardsds. Lanbrix, recently hired as viticulturist, is one of the regions biggest fans of wooly weed eaters. She’s sold on the nutrient-rich manure of the sheep, as well as their ability to keep the vineyards clean. Read more

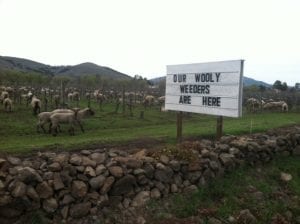

The “Wooley Weeders” are back at Cline Cellars in Sonoma!

According to Cline: “We believe we utilize the most efficient methods towards retaining healthy vineyards by employing the use of organic cover crops, compost teas, crushed volcanic rock and oyster shell, natural mined sulfur and sheep grazing. …To assist in removing harmful weeds from the vineyards, we employ grazing sheep. Hand pulling weeds and an under row cultivator that uproots weeds are often used as well.”

In this fascinating insider’s book, celebrated cookbook author and former chef Joyce Goldstein traces the development of California cuisine from its formative years in the 1970s to 2000, when farm-to-table, foraging, and fusion cooking had become part of the national vocabulary. Interviews with almost two hundred chefs, purveyors, artisans, winemakers, and food writers bring to life an approach to cooking grounded in passion, bold innovation, and a dedication to “flavor first.” She profiles Don Watson and Napa Valley Lamb and Wooly Weeders as early innovators. Read more

HERDED THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE

Don Watson cashes in on sheep labor.

Driving along Wine Country roads, you’ll often spot workers amongst the vines. But winter visitors passing vineyards in Carneros do a double-take when they glimpse some unusual, fur-clad working mothers sauntering through the fields. “The first day they were here, they stopped traffic,” says Linda Champagne, director of hospitality at Artesa Vineyards and Winery.

That’s because these migrant workers are sheep. Last winter, 500 of the ovines munched on weeds at Artesa and other area vineyards while their lambs played among the rows. The sheep also work at Infineon Raceway throughout the year. The live mowing service is the brainchild of Don Watson, a retired CPA-turned-shepherd. His business, Rocky Mountain Wooly Weeders, serves vineyards and farms from Petaluma to Fairfield. the ewes can clear as much as 10 aces a day, taking weeds from 18 inches down to golf-course level. Each flock is accompanied by a Peruvian sheepherder, movable fences, border collies and Great Pyrenees dogs. Besides weeding, mowing, providing manure, and aerating the soil with their hooves, the East Friesian milking sheep are also sold to farms that provide mile to local artisan-cheese producers.

As vineyards emphasize organic and sustainable agriculture, demand for Watson’s sheep has steadily grown. Local growers love the idea because it makes ecological sense and leaves the land healthier and more productive. The pairing of ewe and vineyard seems particularly appropriate in Los Carneros, which, after all, means sheep in Spanish.

Gone to see a man about A Lamb

Chef Mark Sullivan Pays a Visit to a Favorite Farmer

Don is unlike any farmer I’ve ever met. He’s sort of a hero to me,’ says chef Mark Sullivan. “First off, the guy hand delivers his lambs, and they’re wrapped in this pristine white fabric. They’re always stellar. The flavor is clean, the texture, incredibly tender. I’m grateful that he’s out there.”

Read the latest Bacchus Magazine here.

If you own a vineyard in Napa, it’s going to need weeding, and if your vineyard needs weeding, lambs do yeoman’s work, and if you need lambs you call Don Watson and his Wooley Weeders. I don’t own a vineyard but I call Don regularly. Turns out the Wooly Weeders are delicious.

At Camino, each or our meats comes from a single person who specializes in that meat. Don’s our lamb guy. Lamb is underused in this country, because generally it’s subpar. Fatty. Uninteresting. Don’s are another animal entirely: sweet and full of flavor. I pay more and they’re worth it.

Read the Camino cookbook and read more.

In addition to producing lamb, the Watsons grow clover seed and other legume seeds, which are used in vineyards for cover crops. After harvest, the sheep clean up the fields by eating the stubble after the seed has been gleaned.

The flock’s appetite also serves as a source of income for Napa Valley Lamb Co., which offers environmentally friendly mowing services for weed control and fire prevention Since sheep can reach areas that are inaccessible to mechanical mowers, an increasing number of people are employing these ruminant mammals. For example, the Watsons’ sheep graze in the vineyards of Robert Mondavi, eating the weeds so that the vineyard can grow grapes under organic conditions.

“We took a step back and said, “We can’t produce lamb and wool and make it work- we have to look at other sources of revenue from the same production. And that’s why we started the mowing business”, said Watson.

Counting Sheep / Ex-accountant finds way to make his pastoral dreams pay

On a hillside in Sonoma County, two incongruous sounds are mingling in the spring air: the high whine of racing motorcycles and the low baaaaaa of grazing sheep.

The discordant symphony is music to Don Watson’s ears. Since 2007, the ex-CPA has tended some 3,500 sheep at the Infineon Raceway, where they act as animal mowers, clearing nearly 1,600 acres of grass and weeds that would otherwise overrun the motorsports complex’s parking lots and present a perpetual fire hazard in these dry, wind-swept hills.

Putting the sheep to work in this way for his business, Rocky Mountain Wooly Weeders, provides Watson with the perfect complement to his other line of work, running a lamb-and-wool operation called Napa Valley Lamb. In fact, the latter might not exist but for the former.